As a South Australian snorkeler, typically drawn to shallow, inshore waters, I haven’t had first-hand contact with hammerhead sharks. As a child I found them fascinating; their distinctive T-shaped heads an apparent freak of evolution.

In 2014 my interest in hammerhead sharks was renewed. That year, Western Australia introduced a shark culling policy in response to a number of human fatalities following shark bite events over several years. The policy was met with support by some, but also mass resistance. Thousands of people gathered in WA and in solidarity around the country to reject the policy and express their preference for non-lethal shark control measures.

How is this relevant?

While the use of drum lines intended to catch and kill sharks off Western Australia was relatively new and controversial, the use of lethal shark nets in Queensland and New South Wales was a long established practise. I was granted an opportunity to speak at two rallies in opposition to the WA shark cull, and given that I was to speak in Glenelg, South Australia, (and not in WA) I gave the use of other shark control measures in Australia some careful consideration. I thought the audience would benefit from some national context on the topic.

What I discovered was that shark nets entangle and kill a wide range of animals. While they do catch and kill some potentially aggressive pelagic sharks, they also catch and kill many non-target species. Among them were occasional whales, turtles, rays and several species of hammerhead sharks.

This discovery prompted me to read further on hammerheads. I soon discovered that the three species found in Australian waters are all species of global conservation concern. They are: the smooth hammerhead (vulnerable), scalloped hammerhead (endangered) and great hammerhead (also endangered). A full listing of hammerhead sharks and their conservation statuses is maintained by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and can be found in the Wikipedia article: Hammerhead sharks.

So which hammerhead is which?

The common name “hammerhead” can be liberally applied to nine separate species of shark globally. There are eight species in the genus Sphyrna, and one in the genus Eusphyra. Their common names include various hammerheads, scoopheads, bonnetheads and a winghead… all variations on the common theme.

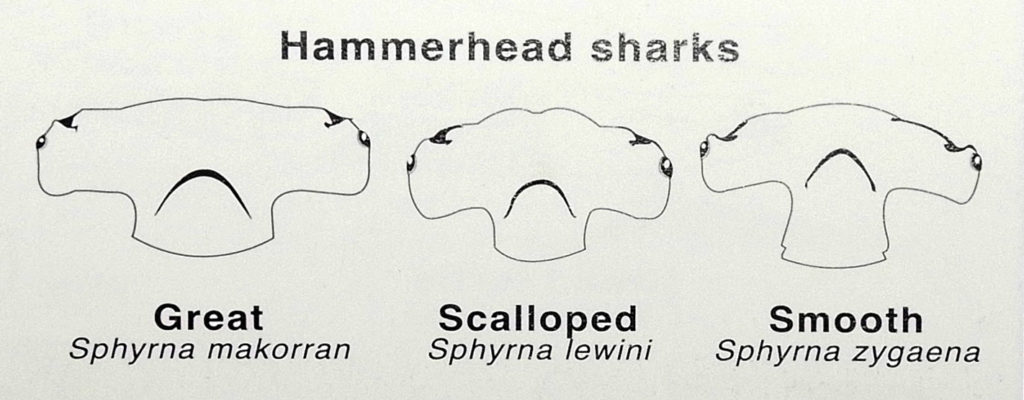

Until recently I was naive to the fine art of telling the three species of hammerheads found in Australian waters apart from one another. I’m happy to say, that changed when I was holidaying in Western Australia. There I stumbled upon a simple guide that draws attention to their physical differences. The shapes of the “hammers” of the smooth, scalloped and great hammerheads are clearly described with simple line diagrams in the book “The Dive Spots of Western Australia” written by Johan Boshoff. I’ve reproduced the image below for the benefit of others researching this topic.

A few days after buying a copy of the book, I found a place to put the hammer guide to good use. My wife Emma and I made a visit to the Museum of Natural History & School of Taxidermy in Guildford with entertainer Tomas Ford and his son Preston. The museum, housed in an old theatre, contains a strange and wonderful private collection of stuffed and cast animals, large and small- shells, bones and curiosities. One whole wall is dedicated to marine species, and further specimens are dispersed within the collection. Among them were three hammerhead sharks (two complete, and one head-only). You can see them in the gallery below.

I saw this as an opportunity to try to help the museum’s curators clarify their specimens’ identities to species level. Using the above guide, the largest hammerhead specimen on display appears to be a young Great Hammerhead. Note the straightness of the hammer. The other two hammerheads on display both appear to be Scalloped Hammerheads. The head of the scalloped hammerhead has three distinctive features: the series of four bumps on the front of the head, the stubby width of the hammer (relative to great and smooth hammerheads) and the curvature of the hammer. The bumps on the front of the smooth hammerhead’s hammer are less pronounced, and number 3, not four- notably absent is the central cleft.

Speaking of elasmobranchs, two others on display at the museum caught my attention. One was incorrectly labelled as a “Banjo ray” but I recognised it as an Angel shark immediately. After some further desktop research, I concluded that this was most likely the Atlantic angel shark (Squatina dumeril) based on its colour. The Australian angel shark is a much paler, sandy colour. This Atlantic species is not known to Australia, so if that’s what it is, it was most likely acquired through trade. The other ray looks like an eagle ray, but I’m not game to make further guesses at the species ID without seeing the top-side of the animal. Not easy to do, when a specimen is hanging from the ceiling in the museum’s foyer!

I would be very interested to learn more about hammerhead occurrence in Australian and South Australian waters. I would love to see any photographs fishers, boaties or divers may have taken of live hammerheads in South Australian waters or of landed catch. I am aware that they are seen in both South Australian gulfs, and the records of the Atlas of Living Australia shows sightings of hammerheads surrounding the entire Australian continent.