Fish identification can be tricky at the best of times. Then there are often new species that were not included in the old fish books. And the scientific names of species are often changing, and even changing back again.

I recently revisited my 2016 article titled “Same Ray Seen Two Months Apart” (It can be found at https://mlssa.org.au/2016/01/09/same-ray-seen-two-months-apart/). It was about my sighting of a ‘stingray’ with part of its tail missing. I had seen what appeared to be the same ray at Port Noarlunga reef, two months apart over 2015-16. I had no idea what species of ray it was, and I wasn’t even going to try to determine what species it was, until now.

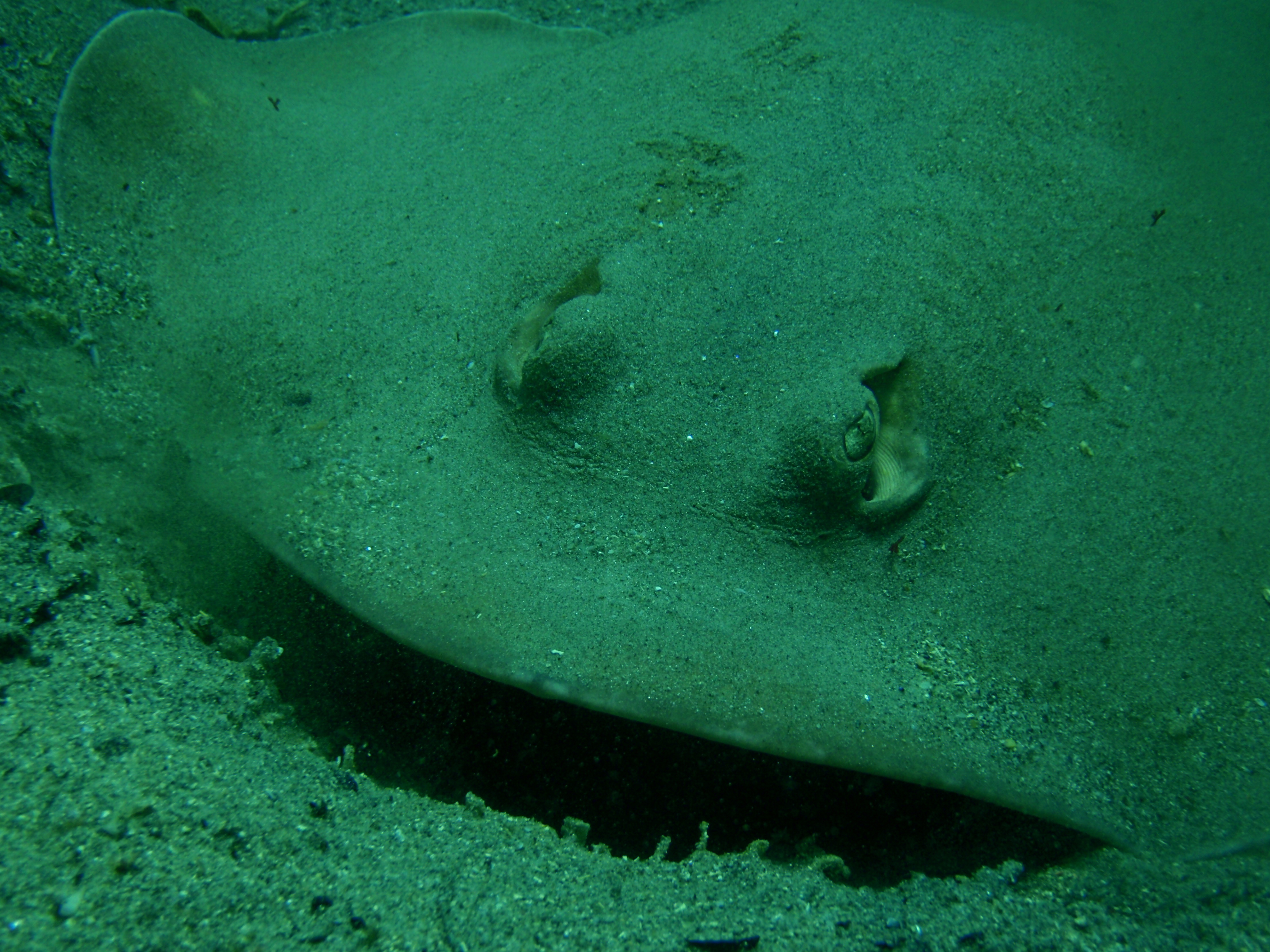

My ‘ray’ at Port Noarlunga

I have been posting some of my photographs on the iNaturalist site, including some underwater photos, especially fish ones. Whilst visiting the site, I noticed a reference to a report about the breeding of the Eastern Shovelnose Stingaree, Trygonoptera imitata. It was titled “Breeding time! – Ken Flanagan has confirmed the breeding time of Eastern Shovelnose Stingarees in PPB (Port Phillip Bay)”. It can be found at https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/australasian-fishes/journal/10180-breeding-time .

I duly read the report and discovered that the Eastern Shovelnose Stingaree was only described in 2008 (by Yearsley, Last & Gomon).

There were some photos of the Eastern Shovelnose Stingaree in the report. I thought that they reminded me of the ray that I had reported seeing twice in two months at Port Noarlunga reef. I decided that I would post photos of that ray on the iNaturalist site seeking identification of it.

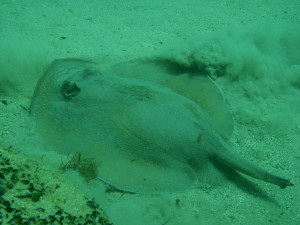

My ‘ray’ at Port Noarlunga

(Photo by Steve Reynolds)

An early ID soon came through, suggesting that it may be a Western Shovelnose Stingaree. “Great!” I thought, thinking that I had correctly seen a similarity in the two species. I then received confirmation that the ray probably was a Western Shovelnose Stingaree, Trygonoptera mucosa.

The Western Shovelnose Stingaree had been described by Whitley in 1939. It is listed as Urolophus mucosus in “Sea Fishes of Southern Australia” by Barry Hutchins and Roger Swainston under the common name of just “Western Stingaree”. The scientific name has now changed to Trygonoptera mucosa and ‘Shovelnose’ has been added to the middle of the common name.

According to the web page at http://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/2631#summary , the Eastern Shovelnose Stingaree is “A large plain-coloured coastal stingaree with a relatively deep-body, a smooth rhomboidal to subcircular disc, two venomous spines, a long fin on the tail and no dorsal fin. The upper surface is brown to dark brown, sometimes with scattered darker and lighter spots, and the underside is pale usually with a broad darker margin.”

This description comes with a warning – “DANGER: a sting from the venomous spines may be excruciatingly painful.”

According to the web page found at http://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/4285 , “The western shovelnose stingaree (Trygonoptera mucosa) is a common species of stingray in the family Urolophidae, inhabiting shallow sandy flats and seagrass beds off southwestern Australia from Perth to Gulf St Vincent. Growing to 37 cm (15 in) long, this small ray has a rounded pectoral fin disc and a blunt, broadly triangular snout. Its nostrils have enlarged lobes along the outer rims and a skirt-shaped curtain of skin between them with a strongly fringed posterior margin. Its tail ends in a lance-like caudal fin and lacks dorsal fins and lateral skin folds. This species is coloured grayish to brownish above, sometimes with lighter and darker spots, and pale below, sometimes with darker marginal bands and blotches.”

Clinton Duffy, a marine scientist working for the New Zealand Department of Conservation, a marine associate at Auckland War Memorial Museum and part-time PhD student in the Institute of Marine Science, University of Auckland had identified my ray as the western shovelnose stingaree. His “principle areas of interest are the taxonomy and conservation biology of sharks and rays, marine protected areas and marine biodiversity”.

Of my ray, Clinton said, “No dorsal fin or lateral cutaneous folds on tail; greyish upper surface with irregular scattered pale (could be yellowish but hard to say what true colour is) and dusky spots – it’s a good fit (with the western shovelnose stingaree) with the description in Last & Stevens (2009). Looks pregnant.”

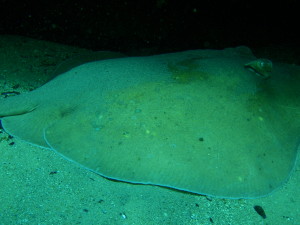

My ‘ray’ at Port Noarlunga

(Photo by Steve Reynolds)

(Reproduction in the western shovelnose stingaree is “aplacental viviparous, with females bearing one or two pups annually”.)

The web page found at http://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/4285 also says: – “Sedentary polychaete worms are by far the most important food source of the western shovelnose stingaree; other benthic invertebrates and the odd bony fish may also be taken.

“Reproduction is aplacental viviparous, with females bearing one or two pups annually in late May or early June. The gestation period lasts one year, during which the mother produces histotroph (“uterine milk”) to nourish her developing embryos.

“The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as of Least Concern, as it faces little to no fishing pressure other than in the northwestern extreme of its range, where it is frequently caught incidentally by trawls. It usually survives to be discarded, though its tendency to abort its young when captured is of concern.”

This photo of an Eastern Shovelnose Stingaree at Queenscliff, Port Phillip, Victoria was taken in December 2016 by Sascha Schulz who visited us earlier this year (2017): –

An Eastern Shovelnose Stingaree at Queenscliff, Port Phillip, Victoria

(Photo by Sascha Schulz)

According to the web page found at http://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/2631#moreinfo, the Eastern Shovelnose Stingaree is “Endemic to south-eastern Australia, from Jervis Bay (New South Wales) south through northern Bass Strait (including Flinders Island) to Beachport (South Australia), and possibly as far west as the Gulf St Vincent (South Australia). Common in Port Phillip Bay and Western Port, Victoria. (It) Inhabits sandy and muddy bottoms in shallow bays, estuaries and inshore coastal waters at depths of about 5-120 metres. The species may possibly occur in deeper waters in South Australia. (Its) Features (are) Disc subcircular, wider than long, anterior edge obtuse; snout fleshy, tip not extended; eye diameter about 20–23% preocular snout length; posterior margin of spiracle angular; about 6 tiny papillae on mouth floor; internasal flap skirt-shaped, posterior angle not extended into distinct lobe; tail length 81–89% disc length; no dorsal fin; caudal fin lanceolate. Size – To 80 cm TL. The largest known specimen measured 793 mm TL, with a disc width of 486 mm (a female). Colour – Uniform greyish-brown or yellowish above, darkest on midline of head, central disc and tail, paler toward disc margin, with a few dark spots scattered irregularly on pectoral disc; centre of tail in juveniles with a blackish stripe from just before the pelvic fin base to the caudal fin. Underside pale over centre of disc, anterior margin, sides and posterior margins of disc similarly darker than central part of disc and tail; pelvic fins with a broad dark margin; some with irregular dark blotches on abdomen; tail uniformly dark. Feeding – Carnivore – feeds mostly on bottom-dwelling invertebrates. Biology – Females give birth to live young. Stingarees are aplacental viviparous, meaning that the embryos emerge from eggs within the uterus and undergo further development until they are born. After emerging from their egg cases, the embryos are initially sustained by their yolk, and later by histotroph, a “uterine milk” produced by the mother.”

It goes on to say that the Eastern Shovelnose Stingaree differs from the Western Shovelnose Stingaree in that “It is much larger than Trygonoptera mucosa (max length 44 cm TL), which also lacks a dorsal fin, and differs in having a shorter prespiracular length.” and “Trygonoptera imitata was previously confused with Trygonoptera mucosa and T. testacea which it resembles in general appearance. The species name imitata is from the Latin imitor, meaning ‘copy’ or ‘mimic’, in allusion to this similarity.”

According to “Breeding time!” at https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/australasian-fishes/journal/10180-breeding-time, “These two images show female Eastern Shovelnose Stingarees, Trygonoptera imitata at Brighton, Port Phillip Bay, Victoria. The photo on the left, which was taken on 6 April 2017 shows a fish that is not pregnant, the fish in the image on the right (photo taken on 3 February 2017) is clearly pregnant.

“Clinton Duffy examined many observations of the species and made the following comments, “I haven’t gone through all of the images but this gives you an idea of what’s there; pregnant females apparent from December to early March; the mature males appear to turn up after the first pregnant females presumably to mate with them as soon as they are post-partum; I have included links to some of Ken’s observations of what appear to be very small, possibly neonate, rays but that probably needs a closer look to confirm. Many of the pregnant rays appear to be associated with cover or rocky substrate but I’m not sure if that’s a real association or not.”

“Last et al, 2009 state that, “Litters of up to 7 pups born annually in February or March ; pupping normally occurs in sheltered waters”.”

Many thanks go to Sascha Schulz and Clinton Duffy for their assistance with these details.

Please add your sighting records to the Atlas of Living Australia. The species page you’re looking for is here: http://bie.ala.org.au/species/CAAB:17d4ff1a:90a3ddd1:0db78a23:8eaf51b7#overview