While this weekend’s scorching hot temperatures kept my wife and I out of the sun for the most part, we couldn’t resist making a late night beach walk down at Glenelg. While the habitats there are highly modified due to breakwater and marina construction, dune removal for coastal development plus stormwater, Patawalonga and treated wastewater inflows, there remains an abundance of life to be observed by anyone with an eye for detail and a nice bright flashlight.

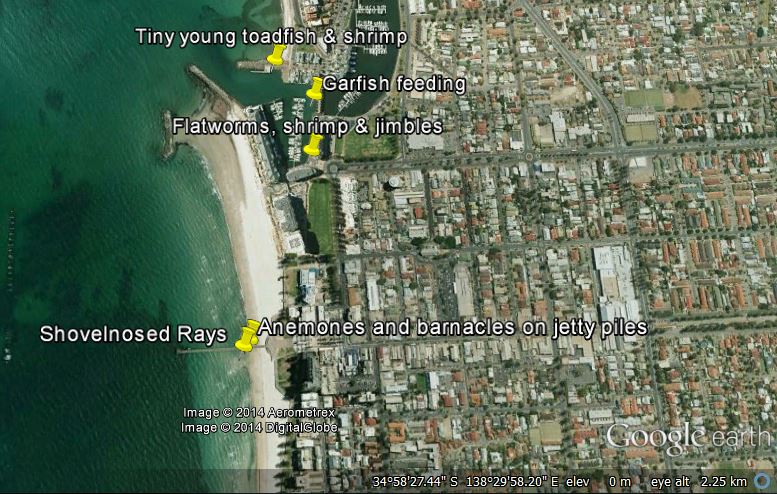

Emma and I began our walk on the north side of the Patawalonga mouth. Taking a quick look along the short jetty at the marina entrance, we noted the poor visibility (about 2-3 metres) and a couple of Western Talma, keeping a low profile. I clambered down the rockwall to photograph a chiton which had been exposed as the tide retreated, but when I arrived at the water’s edge, I was instead delighted to see the smallest Smooth toadfish I have ever encountered, and at least half a dozen of them. Also present were limpets and shrimp with red cuffs. Finding the toadfish in this environment was of interest, as I have previously encountered much older and larger specimens, swimming over or buried in sandy bottom.

Next we crossed the Patawalonga, where our eyes were caught by the little splashes of garfish feeding. These fish swim casually at the surface of the water at night, occasionally darting forwards as they ‘pounce’ on passing prey. Their blue scales shimmer beautifully under torchlight.

On a daytime visit the previous week, I had noted the presence of an interesting little groyne in the south eastern corner of the marina. It resembles a small amphitheatre, is lined with wooden sleepers, and descends right down to the water’s edge. Here we saw more shrimp, a tiny jimble jellyfish pulsing frantically along, barnacles raking the water for food, a few invasive European fanworms at depth and a single Old Wife. There were lots of tiny larvae wriggling about in the water, which was coated with a smokey, oily sheen.

We also spotted two flatworms swimming gracefully in the water, like tiny aquatic flamenco dancers or ballerinas, swirling their skirts. The specimens we observed were no larger than a 10c piece, bright white on one side, and mottled (resembling brown algal turf) on the other. When these worms wish to descend in the water column, they simply stop swimming, and contort their bodies. In this shape they resemble a piece of sinking algal detritus, or maybe a bryozoan. We also watched one of them settle on the algae-encrusted perimeter of the marina and effectively disappear, again by distorting its body and ‘going Bryozoan.’

I was keen to take a look at the Glenelg Jetty proper, and see what was living on the piles and in the sandy inshore habitat adjacent, so we pressed on. After photographing anemones, barnacles and worms on the jetty piles, we observed some larger toadfish cruising about. We also watched a small sand crab bury itself in the sand after being caught in the beams of our torches.

Perhaps the greatest thrills of the night soon followed, when Emma discovered something buried in the sand in about a foot of water. At first we thought it was an octopus, because the only visible parts appeared to be its eyes, which were raised on short stalks and pointed outwards. On closer inspection, we ruled that out, after we observed the pupils were not the slightly dumbbell-shaped slits of an octopus. We also discovered the subtle suggestion of the outline of the animal- which matched another shape I recognised- that of a Shovelnosed Ray.

My first encounters with Shovelnosed rays came last summer, where I saw them on several occasions, including beyond Brighton Jetty in about 3 metres of water (among patchy seagrass) and around dusk at West Beach in the shallows (in approximately 1 foot of water).

Of this specimen, a few interesting observations were made. Firstly, the animal appeared to be buried at quite a shallow depth within the sand, yet there was no sign of the animal’s two dorsal fins. I had noted during my previous encounter off Brighton Jetty that the animal was capable of laying down its dorsal fins, but had not given it much thought at the time. It now seems to me this function complements the animal’s sand-burial camouflage strategy.

While photographing the animal’s eye, I observed that it has the ability to retract its eye-stalks (for want of a better term) essentially pulling its eyes downwards into its head. I suspect this could be another defence mechanism which could make the animals’ eyes less vulnerable to predation.

Any uncertainty about the species identification evaporated after Emma and I encountered another much more active specimen in similarly shallow water, this time slightly north of the jetty. This animal was approximately a metre in length but didn’t stick around for a portraiture session. Instead it turned gently and swam off parallel with the jetty, towards deeper water.

The evening’s adventure came to an end and we crawled back home after 1am. It was still 28 degrees outside. The balmy weather and the diversity of habitats and species sighted made for a comfortable night of delight and wonder by torchlight.