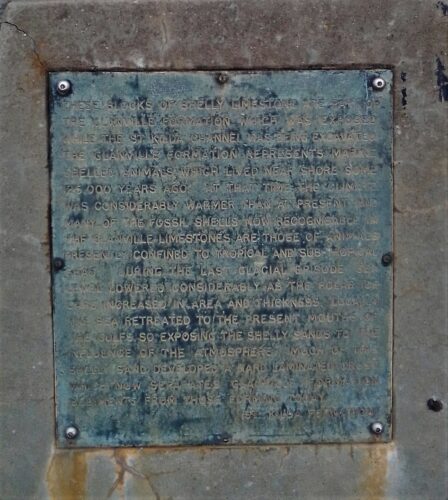

There is a plaque at St Kilda (SA) explaining about the rocks used to build the long breakwater there: –

Certainly, it can be hard to read, but this is what it says (sic): –

“These blocks of shelly limestone are part of the Glanville Formation which was exposed while the st Kilda channel was being excavated. The Glanville Formation represents marine shelled animals which lived near shore some 125,000 years ago. At that time, the climate was considerably warmer than at present and many of the fossil shells now recognisable in the Glanville limestones are those of animals presently confined to tropical and sub-tropical seas. During the last glacial episode, sea level lowered considerably as the polar ice caps increased in area and thickness. Locally, the sea retreated to the present mouths of the gulfs, so exposing the shelly sands to the influence of the atmosphere. Much of the shelly sand developed a hard laminated crust which now separates Glanville sediments from those forming today (St Kilda Formation).”

I found the plaque recently when I checked out this (replica?) anchor nearby: –

The plaque was adjacent to the anchor and it caught my attention whilst photographing the anchor.

According to the web page found at https://www.dit.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/43262/Part_B_Section_21_Geology,_soils_and_contamination.pdf,

“The Glanville Formation consists of marine, grey shelly sand, varying to sandy marl and sandy clay and underlies the St Kilda Formation. The sands are generally loose and uncemented, but the upper portion is often calcreted (or lime impregnated) and oxidised to a variable degree due to its exposure as a land surface during the low sea levels of the last glaciation. Usually the thickness of the Glanville Formation is not more than several metres. The soils generally have low strength except where cemented. The groundwater system present in the Glanville Formation is only partially confined and thus has a similar

phreatic surface to the groundwater system in the overlying St Kilda Formation. Underlying the Glanville Formation is the Pleistocene aged Hindmarsh Clay. This material is predominantly mottled red brown, yellow brown and grey clay but is often sandy, silty, micaceous or gravelly, and it contains lenses of these materials where fluvial influences have been pronounced. The

clay layers are generally stiff to hard, but often have lower strength near the top of the unit due to weathering and/or the presence of a watertable in the overlying sediments. Relict soil horizonation and cyclic layers of carbonate segregations (containing pisoliths, nodules and concretions) are common in the upper 1–3 m, probably indicating past surficial pedogenic processes. …….”

The web page also discusses the St Kilda Formation as follows: –

“The Holocene aged St Kilda Formation consists of a variety of sedimentary materials derived from marine beach, coastal dune, estuarine and backbarrier lagoonal environments of deposition. The St Kilda Formation sediments in the project area were deposited in an estuarine environment and are highly variable. They range from silts, clays and muds to variants rich in organics, shell and sand. The main facies expected to underlie the South Road Superway are the estuarine and lagoonal facies.”

(Facies = “the character of a rock expressed by its formation, composition, and fossil content”.)

Further, “The soil types forming these facies are black to grey to blue-green in colour, and in composition they range from silts and clays to organic layers including peat and fibrous beds, shelly layers and sands. The soils are soft where clayey, loose where sandy, and highly compressible. Shallow saline groundwater is associated with these soils, which also have a fetid odour and acid sulfate potential. The total thickness of St Kilda Formation may vary from less than 1 metre to nearly 10 metres.”

The beach at St Kilda

Above is a photo of the beach at St Kilda, with the breakwater on the left. The container terminal cranes at Outer Harbor can be seen in the background. There are several black swans in the shallow water off of the beach.

Thanks Steve.

The parts about the soils silts clays and calcrete are of particular interest to me because I never know how to describe or label the non calcareous substrates scattered around inshore Yankalilla Bay.

The mostly grey rather porous and fragile yet somewhat clay like gungy stuff that is usually evident along seagrass scarps for example.

It is scarcely firm enough to call rock substrate but too firm to call soft bottom.

Cheers

David