Fish are now thought to feel pain in a way that is comparable to land animals. Although not all scientists agree, the consensus that fishes actually do suffer like us is fast approaching. There is also much work being done on fish cognition and emotion, which shows that fish “have complex emotional lives and relations with others”.

Our July 1988 Newsletter (No.132) included two articles concerning the belief that fish, contrary to general opinion, actually do feel pain. The two articles were titled “Fish Have Feelings” and “Fish Feel Pain”. I had written the first article myself whilst the other was written by the Animal Liberation group. The following month our newsletter (August 1988, No.133) included a letter from Geoff Mower on the subject to the Editor, and my response. I agreed at the time that Geoff had “quite rightly shot all of my suggestions down in flames”. Much later, however, in our July 2003 Newsletter (No. 301), I wrote another article titled “Fish Do Feel Pain”. In that article, I wrote “I now feel a little vindicated since the announcement of new findings that fish do feel pain. …. Although I don’t yet know the details of the new findings concerning fish pain, it is nice to know that there is still some belief that fish do in fact feel pain.”

These latest words followed the publishing of an article titled “Rainbow Trout Really Do Feel Pain, Study Says” By Roger Highfield, Science Editor (Filed: 30/04/2003, Telegraph Group Ltd )

According to the article, “Evidence that fish do indeed feel pain is published today, a finding that will reopen hostilities that have raged for decades between anglers and animal rights activists.

Earlier this year, an American study seemed to let anglers off the hook: Prof James Rose of the University of Wyoming concluded in the journal Reviews in Fisheries Science that awareness of pain requires consciousness, which fish do not possess.

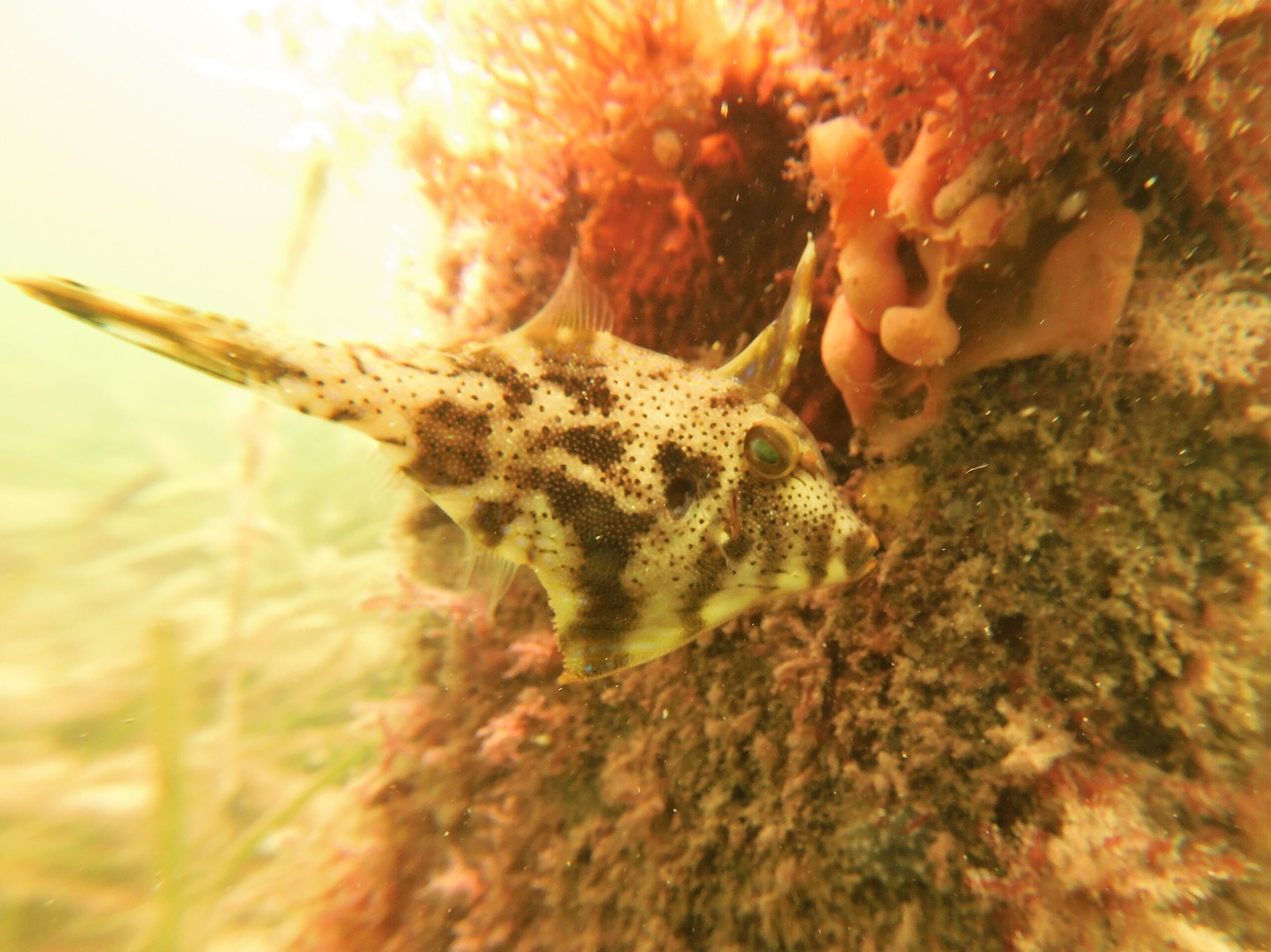

Now a study of rainbow trout suggests that they not only possess the equipment to feel pain, but react in a way consistent with suffering.

This is the first conclusive evidence indicating pain perception in bony fish such as trout, salmon, cod and haddock, according to one of the authors, Dr Lynne Sneddon, who led the research at the Roslin Institute, near Edinburgh, and is now working in Liverpool.

“The study shows that the trout not only possesses nerves that can detect pain but also shows the kind of behavioural changes that would be associated with discomfort and pain in ‘higher animals’,” said Dr Penny Hawkins, senior scientific officer of the RSPCA.

“All vertebrates should be given the benefit of the doubt and assumed to be capable of suffering.”

Not everyone is convinced. Rodney Coldron of the National Federation of Anglers said yesterday: “We believe the Prof Rose study went into more depth and supports our view that fish do not feel pain.”

Prof Rose told The Telegraph that the study “in no way justifies a conclusion that these fish have a capacity for the conscious experience of pain”, attacking it as “anthropomorphic speculation”.

The new findings are published by Dr Sneddon in Proceedings B, a journal published by the Royal Society. The work, also at the University of Edinburgh, was funded by the Biotechology and Biology Research Council.

Based on her findings, Dr Sneddon said yesterday that she had no problem with anyone who caught and quickly killed a fish for eating. But she drew the line at catching fish and throwing them back, which could cause suffering. “Some studies have shown high mortality after angling.”

Her study, undertaken with Dr Victoria Braithwaite and Dr Michael Gentle, found that rainbow trout have nociceptors – nerve receptors that respond preferentially to tissue damaging stimuli. “We found 58 receptors located on the face and head of the rainbow trout,” said Dr Sneddon.

The 18 “polymodal nociceptors”, which responded to all potentially painful stimuli in the trout, were the first to be found in fish and had similar properties to those in humans, said Dr Sneddon.”

I am recounting all of the above because Carl Charter recently shared a post on Facebook –

“Many people assume that fishes do not feel pain, or lack the abilities that land animals possess. However, these views are increasingly being shown to be erroneous. Pioneering work by scientists such as Lynne Sneddon and Victoria Braithwaite have shown that fishes feel pain in a way that is comparable to land animals. And while not all scientists agree, we are fast approaching the consensus that fishes indeed do suffer like us. In addition, there is much interesting work being done on fish cognition and emotion, including by Australian-based scientist Culum Brown. This research increasingly shows that fishes have complex emotional lives and relations with others.”

The post was linked to information written by the animal protection institute Voiceless –

“FISHES: THE NEXT WAVE OF ANIMAL ADVOCACY?” by Dinesh Wadiwel (May 27, 2019)

“Public perceptions of animals have changed a lot in recent decades. In large part, credit for this is due to a fierce global animal advocacy movement which has worked to raise awareness that animals are sentient beings who are owed flourishing lives. We have a long way to go, but certainly improvements in welfare, rights recognition and changing consumer decisions are an outcome of a very strong advocacy movement.

However, fishes often escape the attention of animal advocates. High profile animal advocacy campaigns tend to focus on land animals used for food, amusement or experimentation. This means that apart from exceptional cases, such as whales or dolphins, public pressure for improved welfare or recognition of rights is usually focused on land based animals. Indeed, there seems to be an almost uncanny silence when it comes to thinking about fishes – they are, as Peter Singer has described, the “forgotten victims on our plate.”

This is unfortunate, since humans use fishes more than any other animal. UN Food and Agriculture Organisation figures suggest that humans slaughtered close to 75 billion land animals in 2017 for food. This figure is sobering for all animal advocates. However, human use of fishes for food far outstrips our use of land animals. Fishcount.org.uk estimates that globally each year up to 2.3 trillion wild fishes are captured in our seas. We have also seen a massive expansion in aquaculture (or “fish farms”) globally, with the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation announcing that in 2014 “the aquaculture sector’s contribution to the supply of fishes for human consumption overtook that of wild-caught fish for the first time.” Globalised production and processing of fishes mean that they constitute some of the most traded food commodities on the planet. Large numbers of fishes are captured for subsistence and recreation globally, and fish are increasingly found today in labs as test subjects.

In many contexts, particularly industrial-scale wild fish capture, basic welfare precautions are completely absent. For example, most wild fishes caught globally die through asphyxiation. These animals are left on the deck or on a line to suffocate. Death through asphyxiation is incredibly cruel for fishes. Research has indicated that some fishes, such as sea bass, will take up to 60 minutes before they lose consciousness. In industrialised wild fish capture, many fishes suffer severe injuries when hauled up by nets, including through burst swim bladders as a result of rapid pressure changes, or being crushed or injured by other fish, when scooped or “brailed” onto the deck of the ship.

Many people assume that fishes do not feel pain, or lack the abilities that land animals possess. However, these views are increasingly being shown to be erroneous. Pioneering work by scientists such as Lynne Sneddon and Victoria Braithwaite have shown that fishes feel pain in a way that is comparable to land animals. And while not all scientists agree, we are fast approaching consensus that fishes indeed do suffer like us. In addition, there is much interesting work being done on fish cognition and emotion, including by Australian-based scientist Culum Brown. This research increasingly shows that fishes have complex emotional lives and relations with others.

The implications of this emerging science on fish sentience, emotion and cognition is profound. For fisheries, the implications are perhaps most significant, since basic welfare measures are not compatible with industrial fisheries. It is certainly very difficult to see how wild capture fisheries – which typically involve hunting down schools of fish, netting them, and hauling them onto boats to be left on deck to die – could ever be reformed to meet minimal welfare standards. This is perhaps why there remain very strong economic interests in maintaining the status quo.

However, there is an important message here for animal advocates too, who themselves appear to have also forgotten about fishes. For animal advocates there is now an important challenge in building advocacy for sea creatures. Fishes are the most highly utilised animals on the planet; yet welfare and rights protections are at the lowest level for these creatures, and these animals are frequently near the bottom rung of public perception. There is an urgent need for advocates to help build public awareness around the lives of fishes.

And work has already started. Internationally, activists have been building an annual World Day for the End of Fishing on March 30. Advocacy organisations have also started to create better resources which highlight the welfare and rights of fish.

Perhaps fortuitously, animal advocates are not alone in being concerned about how fish are used today. Fisheries in particular have generated deep concerns for labour rights activists in relation to the use of low wage and forced labour in fish capture and processing. Fisheries have attracted a lot of attention, in part because of the unsustainability of industrial wild fish capture, and the growing environmental problems associated with aquaculture, such as the impacts of fish escapes. Indeed some of these concerns have led commentators to call for consumers to “stop eating fish.” Given this growing chorus of concern, the timing is perfect for us all to work harder towards ending our mass scale violence towards fishes.

(Editor’s note: You may have noticed that the term ‘fishes’ is used in this blog instead of the word ‘fish’. This wording has been used to capture the fact that there is a large diversity of species classified as ‘fish’, so it is more accurate when speaking generally about all species of fish to refer to them as ‘fishes’.)”

In today’s print media is an article about how shocked everyone is about a video posted on Facebook or similar platform showing a live kitten being fed to a pet python. In SA its illegal to feed any pet animal with live food. I find the hypocrisy gobsmacking.

It is legal to use live fish eg Australian herrings (Tommy Ruffs) as bait when fishing, eg trolling and surf casting.

Primary school biology texts say that fish are vertebrate animals and that all vertebrate animals feel pain.

So where is the legislation proposing that live bait usage be banned?

Nowhere, or maybe hidden away in a file marked ” Don’t go there, its political suicide “.

Even the RSPCA keeps a very low profile (akin to ” no comment”) on the topic because while every veterinary surgeon knows that fish feel pain the RSPCA’s PR team has to prioritise maintaining the glowing public reputation the organisation enjoys ahead of endorsement of scientific fact .I don’t blame them, because they rely on donations and bequests to fund their work with terrestrial creatures. That is pragmatism, and with roughly one fifth of SA residents being recreational fishers, the organisation philanthropic funding would drop (initially, but I believe people like me, who never donate to the RSPCA because we know how impotent they are at preventing cruelty to marine life especially fish, would start donating and soon fill the breach.Example: my late mother donated regularly to the RSPCA( among other good cause advocacy

groups eg Red Cross) but I ceased her RSPCA donations following the execution of her last will and testament decades ago,mainly because fish feel pain just like dogs and cats.

So to all those shocked and distraught cat lovers out there, I think that video (which I have not seen, only read about) could have been done by someone with better understanding and indeed a more caring mindset for one of 2 reasons:-

To express their frustration at the obscene reluctance of any political parties to enact effective cat control laws, which are desperately needed to reduce our nation’s escalating yes escalating wildlife extinction rates in 2021,

O,r to make the point that people think nothing of feeding live mice to their pet cats (that is what you do when you own a cat, unless you stop it from bringing killed rodents to your door, which few owners will admit…another inconvenient truth) but will happily stick a hook in a live scalefish and hope a bigger fish will grab it. While it is still alive and suffering a slow and painful dying process.

By the way, kittens catch and torture baby snakes, too. And lizards and birds and frogs..

KITTENS ARE LITTLE CATS. THEY ARE FAST LEARNERS, SOON TO BE BIG CATS.

And our neighbour’s cat kills birds daily in our garden. A cat run (as approved by the RSPCA) promised by the neighbour never eventuated.