I first heard about terms such as ‘symbiosis’ and ‘mimicry’ when I began researching for my “The Colour of Fish” articles in 1979. I probably also read about fish cleaners for the first time back then.

I discussed symbiosis in my 1980 Journal article “The Colour of Fish”, saying “Symbiosis exists between clownfish and some sea anemones. The stinging tentacles of the anemone protect the fish from predators. It is believed that the clownfish, with their conspicuously colourful bodies, attract would-be predators into their host thus providing food for the anemone.”

The article went on to describe colour mimicry before stating, “Mimicry is most obvious when fish use their resemblance to other fish to trick predators or victims. An example of pseudopisematic colouring (a dangerous fish mimicking a harmless one) occurs with cleaner fish.” (As stated above, researching this this was probably my first experience regarding cleaner fish.)

“The blue streak cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus) is mimicked by the sabre-toothed blenny (Aspidontus taeniatus) which has a similar colour pattern to the wrasse. The blenny seems to betray the trust that other fish have in the wrasse. It mimics the wrasse’s swimming action so as to come close to the unsuspecting fish allowing itself to be cleaned. The blenny then rushes at the victim and rips off a scale or tears out a piece of flesh. Fortunately, this ‘disguise’ only fools younger, inexperienced fish, for the older ones learn to distinguish the blenny from a cleaner wrasse.”

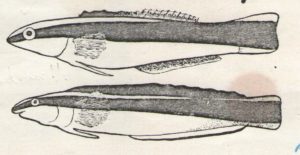

Top – The blue streak cleaner wrasse, Labroides dimidiatus

Bottom – The sabre-toothed blenny, Aspidontus taeniatus

(Drawn by Katrina Bishop – Source: MARIA Journal Vol.1, No.5, Sept. 1980)

“Some fish are able to change colour and body markings quite dramatically in order to attract the attention of a cleaner wrasse. The wrasse is able to interpret such signals. A unicorn fish, for example, changes colour to show up irregularities of skin in order to assist the cleaner. At the same time, cleaner fish themselves have colourful patterns which make them distinctive to fish wishing to be cleaned. Fish needing a clean may become darker so that parasites are more easily seen. Cleaning situations are popular with photographers, as colour patterns adopted by fish being cleaned are unique at that time.”

Bluethroat wrasse at a cleaning station?

(Taken at Port Noarlunga reef by Steve Reynolds)

I still have some of my research notes, which have been placed in to our “Colours of Fish” file (mlssa No.3024) in our library. My notes read, “Cleaner fish (have) striking colouration (that is) easily recognised by all fish. Some fish imitate cleaners so that they can approach other fish and take a quick bite. They tend to imitate the young cleaners whose (black/blue) bands are more pronounced. (It is) important that (there are) not too many imitators which would destroy (the) trust that fish have in (fish) cleaners.”

I also still have some of my references regarding both symbiosis and mimicry in the “Colours of Fish” folder. Fish cleaners also get a mention in some of those references, including “The Colors of Tropical Marine Fish” and “Pigmentation in Fish”.

A folder in our library is full of ‘relevant’ pages from one of those Fishing Encyclopedias. Two of those pages are about cleaner fish. They discuss cleaning stations, sex change in cleaner fish and mimicry.

Regarding cleaning stations, it is stated, “Research carried out on cleaner fish found that from one to three cleaner fish normally occupy one of their fixed ‘cleaning stations’ which are located at depths of one to three metres. These beauty parlours are usually more densely distributed on the windward side of reefs and it was also observed that cleaner fish move from one station to another. It is also not unusual on some occasions for a number of larger fish to queue up for their regular cleaning job. Apart from any diet of parasitic matter, cleaner fish feed occasionally on free-swimming crustaceans.”

Regarding sex change, it is stated, “Well-defined groups of blue streaks have only one totally dominant male; the remainder are a harem of females. When the male disappears, his place is taken by the most dominant female within one hour or so. This fish changes sex and becomes the new, aggressive male of the group.”

It went on to state, “Scientists studying cleaner fish also found that certain cleaner fish had distinct preferences for cleaning certain species of fish and the different host fish knew which cleaner fish to visit if it wanted to be cleaned. One cleaner fish was observed to only clean goatfish while another only serviced the damsel fish.”

Regarding mimicry, the same paper stated, “Cleaner fish also have their mimics; small fish which have evolved similar colour patterns and are therefore afforded the same immunity as cleaners but perform no cleaning duties. The opportunistic blennies are one species which imitates the colour patterns of cleaner fish and then tries to bite chunks of skin and fin off the host fish.” More on this later.

As I am now researching fish cleaning behaviour more closely, I have found more references on the topic in my own library of books. My Lonely Planet book titled “Diving & Snorkeling Maldives” by Casey Mahaney & Astrid Witte Mahaney includes a page on cleaning stations (page 73). It reads: –

“A Clean Break – Symbiosis occurs throughout the marine world – associations in which two dissimilar organisms share a mutually beneficial relationship. One of the most interesting in these relationships is found at cleaning stations, where one animal (the symbiont) advertises its grooming services to potential clients with inviting, undulating movements. Often this is done near a coral head or, particularly in the Maldives, beneath an overhang.

“Various species of cleaners such as wrasses and shrimp care for customers of all sizes and species. Larger fish such as sharks and mantas generally frequent cleaning stations serviced by angelfish, butterflyfish and larger wrasses, while turtles often seek out herbivorous tangs eager to rid the turtles of their algae buildup.

“Customers hover in line, waiting their turn. When the cleaner attends to a customer – perhaps a grouper, parrotfish or even moray eel – they often enter the customer’s mouth to perform dental hygiene and may even exit through the fish’s gills. Although the customer could have an easy snack, it would never attempt to swallow the essential cleaner. The large fish benefit from the removal of parasites and dead tissue, while the cleaners are provided with a meal.

“If you carefully approach a cleaning station, you’ll get closer to many fish than is normally possible and observe interesting behaviour not seen anywhere else on the reef.”

(The accompanying photo shows a shrimp cleaning around the mouth of a moray eel.)

“Exploring Hanauma Bay” by Susan Scott & David Schrichte discusses the Hawaiian cleaner wrasse, Labroides phthirophagus. “This 4-inch-long wrasse picks parasites and mucus off other fish. This species is found only in Hawaii, but similar-looking cleaner wrasses are found throughout the world’s tropical oceans.”

The accompanying photo shows the Hawaiian cleaner wrasse, Labroides phthirophagus, just above a Saddle wrasse, Thalassoma duperreyi. Another photo on the same page (p.38) shows a Hawaiian cleaner wrasse cleaning an orangeband surgeonfish. The text reads, “Cleaner wrasses hang out in specific areas called cleaning stations that larger fish visit, holding still while the cleaner does its work. Some researchers theorize that fish line up for this service not to get rid of parasites but to get a good-feeling rub from the fins and mouth of the cleaner wrasse. The cleaner in this photo gets a mucus and/or parasite meal from an orangeband surgeonfish.”

The photo on the opposite page (p.39) shows a Hawaiian cleaner wrasse in the mouth of a whitemouth moray eel, Gymnothorax meleagris. The text reads, “An eel opens wide to get its mouth or teeth cleaned by this cleaner wrasse. Look for wrasse cleaning stations in small open spaces close to the reef.”

A photo on page 46 shows a convict surgeonfish, Acanthurus triostegus, being cleaned by a Hawaiian cleaner wrasse. The text reads, “Here a Hawaiian cleaner wrasse picks parasites and mucus from the gills of a willing convict surgeonfish.”

A photo on page 48 shows a Hawaiian cleaner wrasse cleaning a manybar goatfish, Parupeneus multifasciatus. The text reads, “In this photo, a Hawaiian cleaner wrasse picks parasites and scales from the skin of a manybar goatfish.”

A photo on page 110 shows a barberpole shrimp, Stenopus hispidus, cleaning a yelowmargin moray eel, Gymnothorax flavimarginatus. The text reads, “Barberpole shrimp sometimes clean fish. This one probes a yelowmargin moray eel’s face.”

The Hawaiian cleaner wrasse can be found on page 164 in “Hawaii’s Fishes – A Guide for Snorkelers and Divers” by John P Hoover. There are four photos on the page. One photo shows two adult Hawaiian cleaner wrasse, one shows a subadult, one shows a juvenile and another one shows yellowfin goatfish, Mulloidichthys vanicolensis, posing to be cleaned.

The Hawaiian cleaner wrasse is described as follows: –

“These little fish glow with color. Adults of both sexes are yellow, blue and magenta with a broad black stripe that widens from head to tail; juveniles are all black except for an intense blue or purple line along the back. Cleaner wrasses of the genus Labroides (five species in the Indo-Pacific) generally make their living by picking external crustacean parasites, dead tissue, and mucus from the bodies of larger fishes. The Hawaiian cleaner wrasse does the same, feeding most heavily on mucus. Individuals or pairs of these fish, but sometimes as many as five, establish permanent territories, typically near a prominent outcrop or under a ledge, attracting customers by flaring the tail fin and swimming with a conspicuous up-and-down bobbing motion of the rear body. Fish which come to be cleaned often assume odd postures (typically head up or down and fins flared) as the wrasses work them over. Often, they will change color, becoming either lighter or darker, possibly to make parasites stand out. Multiple fish waiting to be cleaned will sometimes form a line! Occasionally a cleaner will enter the mouth of a large predator with apparent impunity. At night, cleaner wrasses often encase themselves in thick mucus, as do some parrotfishes. The mucus is secreted by glands in the gill cover and might have antibiotic properties. The Hawaiian cleaner wrasse will not eat in captivity and eventually wastes away. The scarcely pronounceable species name (phthirophagus) means “louse eater”. “

Regarding cleaner fish mimicry, as stated earlier, a folder in our library contained a paper which stated, “Cleaner fish also have their mimics; small fish which have evolved similar colour patterns and are therefore afforded the same immunity as cleaners but perform no cleaning duties. The opportunistic blennies are one species which imitates the colour patterns of cleaner fish and then tries to bite chunks of skin and fin off the host fish.”

Page 7 of “Hawaii’s Fishes – A Guide for Snorkelers and Divers” describes how “Many fang blennies (Blenniidae) feed exclusively on mucus or bits of scale scraped or nipped from the sides of larger fish”. “Sometimes called “hit and run blennies”, these tiny predators make sneak attacks on their larger victims, sometimes relying on mimicry to approach within striking distance. Most remarkable is the Mimic Blenny (Aspidontus taeniatus), an almost exact double of the common Bluestreak Cleaner Wrasse of the Indo-Pacific (Labroides dimidiatus). The mimic even swims with the wrasse’s curious up-and-down dancing motion. When a fish approaches the blenny to have its parasites removed, it loses a bit of skin or scale instead. Although neither of these fishes occurs in Hawaii, juveniles of the Ewa Fang Blenny, an endemic fang blenny, often mimic juveniles of the Hawaiian cleaner wrasse.”

The Ewa Fang Blenny, Plagiotremus ewaensis, is described on page 10 of the book as follows: –

“This colourful fang blenny varies from black to orange to reddish, usually with two dark-edged blue horizontal stripes. It feeds on the scales, skin, and mucus of larger fishes. Its mouth, underslung like that of a tiny shark, contains two long fangs used only for defense. Small individuals, often black with blue stripes, can resemble juvenile Hawaiian cleaner wrasses and almost certainly use the resemblance to their advantage.”

The habits of the Gosline’s Fang Blenny, Plagiotremus goslinei, are said to be similar to those of the Ewa Fang Blenny. The Ewa Fang Blenny is also described on page 121 of “Exploring Hanauma Bay” thus: –

“This 4-inch-long fish hovers just above the reef waiting for larger fish to pass by. When that happens, the blenny strikes at speed, nipping off scales and mucus.”

I seem to have mainly been discussing cleaner mimics now, but the subject is a big part of the topic. “The Reader’s Digest Book of the Great Barrier Reef” discusses Australian cleaner fish in some detail. The blue tuskfish, Choerodon schoenleinii, is shown having its head picked clean of parasites by the blue streak cleaner wrasse, Labroides dimidiatus.

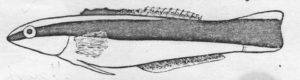

The blue streak cleaner wrasse, Labroides dimidiatus

(Drawn by Katrina Bishop – Source: MARIA Journal Vol.1, No.5, Sept. 1980)

The blue streak cleaner wrasse is also shown inside the mouth of a sweetlip(s), Plectorhynchus chaetodontoides. It is also shown in one photo on page 274 exiting the mouth of another sweetlip(s) and entering the gills of a batfish, Platax orbicularis in another photo. The captions read, “The cleaner wrasse has evolved a habit of taking parasites off the skin of other fishes. A large fish, such as this batfish, will seem quite relaxed as the cleaners pick over its skin and teeth and poke about in its gills.” and “This blue-streak cleaner is emerging from the mouth of a grey sweetlips where it has been acting as ‘dentist’, removing parasites, growths and food scraps from its teeth and pharynx. Although cleaner fish forage for shrimps and worms among the coral, a good proportion of their diet consists of parasites of other fishes, dead scales and tissues, and fungus growths. They perform a valuable service and seem essential to the health of a coral reef fish community. All coral reefs have cleaners of some variety, and where the cleaners have been experimentally removed other resident fishes have either moved away or died, and those that remained became diseased.”

Symbiosis and cleaner fish are both discussed on this page thus: –

“Living together – Within the teeming diversity of plants and animals that cohabit on a coral reef there are myriad examples of animals and plants that have together evolved intricate relationships and interdependencies. Coral reefs owe their existence to the symbiotic relationship between the stony corals and the single-celled algae called zooxanthellae that live within the coral’s tissues.

“One of the most common and most interesting ways in which organisms coexist on the reef is the mutually benefiting relationship of symbiosis. Other relationships are also common in coral reef waters, such as parasitism, where one organism may harm or even kill the other, known as the host, and commensalism, where one organism lives on or inside another, to its own benefit but without apparent harm to the host.

“The dancing cleaners – Within the fish world there are many good examples of symbiosis. In tropical waters there are countless minute organisms which live in – and on – fishes and there is a guild of other fishes, and shrimps, which have evolved as ‘cleaners’.

“A small, elongated blue and white wrasse can often be seen dancing and gyrating in the water over some prominent landmark. Known as cleaners, these fish have specialised in removing growths and parasites from the skin, mouth and gill chambers of other fishes. The special swimming motion serves to identify them and to advertise their presence.

“The area where they perform their trade is known as a cleaning station and fishes that live in the locality, ranging from the small gobies to the large grouper and even manta rays, will visit this locality periodically to be serviced. The relationship between the cleaners and their ‘hosts’ is highly evolved as the host completely turns off any predatory instincts allowing the cleaner to swim unharmed into the mouth and gill chambers – a quick snap and it could be a tasty morsel. The cleaners are obviously performing a valuable service as fishes are known to travel considerable distances, perhaps a couple of kilometres, to attend these cleaning stations. Some experiments have indicated that the removal of the cleaners soon leads to a noticeable drop in the abundance and richness of the fish community of an area, and those fishes that remain are often badly infected with fungal growths, ulcers and frayed fins.

“In the Caribbean Sea, the dominant cleaner is a small blue and white goby of the genus Elacatinus and, interestingly, aquarium fishes collected from Pacific reefs instantly recognise this Caribbean cleaner and solicit its services – cleaning symbiosis has obviously been around for a long time.

“A number of coral reef shrimps have also formed a guild of cleaners and advertise their presence by waving their long white antennae from the entrance to caves. Fish seeking their service come and ‘present’ themselves and, as in their relationship with the cleaner fish, allow the shrimps to enter their mouth and gill chambers free of any risk of predation. The shrimp nimbly skips over the fish removing parasites and fungus from the scales, gills and around the teeth of the host.”

The next page, opposite (page 275), shows shrimps cleaning a cardinal fish, Apogon species. The text reads, “The delicate behaviour of the shrimps seems out of character in the ‘eat or be eaten’ underwater world. But this shrimp is happily cleaning fungal growths from the head of the cardinal fish. These shrimps are very abundant around coral reefs and when not cleaning fishes they are often observed ‘hanging about’ at the entrance to small caves and holes in the reef.”

A false cleaner fish, Plagiotremus rhinorhynchos, is shown on page 249. The text reads, “Some small blennies mimic the cleaner wrasse. They do this by looking the same, and performing a similar dance. Fishes go to them expecting the comfortable grooming of their usual cleaner – instead the false cleaner rushes at them and takes a solid bite of fin or skin. Some species, such as the false cleaner, Aspidontis, have huge lower canine teeth. This false cleaner lacks the huge canines, but still manages to exact its pound of flesh. It has also been known to bite swimmers.”

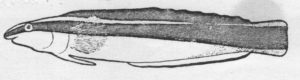

The ‘false cleaner fish’ the sabre-toothed blenny, Aspidontus taeniatus

(Drawn by Katrina Bishop – Source: MARIA Journal Vol.1, No.5, Sept. 1980)

The “World Atlas of Marine Fishes” by Kuiter and Debelius shows a pair of blue streak cleaner cleaner wrasses, Labroides dimidiatus in the mouth of a large grouper. The blue streak cleaner wrasse, Labroides dimidiatus, is said to occur in the Indo-West Pacific, Indonesia, Fiji and Western Australia. The false cleaner fish, Plagiotremus rhinorhynchos, is said to occur in the Indo-Pacific and Indonesia. The sabre-toothed blenny, Aspidontus taeniatus, is said to occur in the Indo-Pacific. The Hawaiian cleaner wrasse, Labroides phthirophagus, is said to only occur in Hawaii. Another cleaner wrasse called Labroides pectoralis is said to occur in the West Pacific, Western Australia and Indonesia. Another cleaner wrasse called Larabicus quadrilineatus is said to occur in the Red Sea and Egypt. Another cleaner wrasse called Diproctacanthus xanthurus is said to occur in the West Pacific and Indonesia. Another cleaner wrasse called Labropsis manabei is also said to occur in the West Pacific and Indonesia. There may be others, but further research would be required to find out.

More than 150 observations of the blue streak cleaner wrasse can be found on the iNaturalist Australasian Fishes site at https://www.inaturalist.org/ .

The late Neville Coleman may be regarded as a pioneer regarding fish cleaning studies in Australia, particularly in tropical waters. He discussed each of symbiosis, mutualism and cleaner fish & shrimps in his 1993 book “Australian Fish Behaviour”, but he only discussed tropical species.

In his book “Coastal Fishes of South-eastern Australia”, Rudie Kuiter says that Western Cleaner Clingfish have been “Regularly observed cleaning other fishes, probably feeding on small parasites”. He also says that the fish that the Eastern Cleaner Clingfish, Cochleoceps orientalis have been observed cleaning most often include boxfishes, porcupine fishes and morwongs. Rudie also said in his book that Pencil Weed Whiting, Siphonognathus beddomei, were “occasionally observed cleaning other fishes”.

The activities of Cleaner Wrasse, Labroides dimidiatus are described in detail in Rudie’s book as follows: –

“Specialised feeders, picking parasites off or attending to wounds of other fishes. Individuals choose strategic point on reef, often cave or elevated part of reef, to which other fishes come for service. Such places are called cleaning stations. . . Large predators (are) common customers. They assist by spreading their fins and opening mouth to allow wrasses to clean teeth and gill rakers, often by swimming through mouth and gills. Unfamiliar or new visitors (are) greeted with up-and-down dance-like motion which appears to assure safety of Cleaner Wrasse”.

Top – The (blue streak) cleaner wrasse, Labroides dimidiatus

Bottom – The False Cleaner fish (or Mimic Blenny), the sabre-toothed blenny, Aspidontus taeniatus

(Drawn by Katrina Bishop – Source: MARIA Journal Vol.1, No.5, Sept. 1980)

The False Cleaner fish (or Mimic Blenny), Aspidontus taeniatus, is also discussed in the book. These imposters feed “by biting unsuspecting prey, taking mainly bits of fin; more experienced fishes learn to recognize the imposter and often chase it”. It is interesting to note that the False Cleaner fish (1834) was described some five years before the Cleaner Wrasse (1839).

We hear that tropical anemone fish, or clown fish, form a relationship with sea anemones. We also hear how each fish becomes immune to the stinging tentacles of the anemone by first receiving minor stings, adopting a particular swimming posture, and producing a protective mucous coating. But what about shrimps which live on sea anemones? How do they manage this? Neville Coleman’s book “Australian Fish Behaviour” says that some shrimps, such as Holthuis’ commensal shrimp, Periclimenes holthuisi, live amongst sea anemones. Holthuis’ commensal shrimps in anemones display as fish cleaners. It seems that they will lure clients well within contact of the anemone’s tentacles, yet the clients are not harmed at all. Small fish have been observed hovering amongst the stinging tentacles while being cleaned by the shrimp. Although the fish must be quite careful around the anemone, the anemone makes no attempt to sting the fish at all.

All the above relates only to tropical species of fish cleaners. Our knowledge of temperate water species, especially in South Australian waters, is still in its infancy, but we can use the knowledge regarding tropical species to assist with ongoing studies regarding temperate species.

There is a nice little section in Neville Coleman’s book “Australian Fish Behaviour” about cleaner fish and shrimps. It raises the following questions, which may be applied to SA fish cleaners: –

How many species are full-time, part-time or opportunistic cleaners and which species are they?

Does cleaning occur during the day or the night and by which species?

What signals are used by different cleaners and clients wishing to engage in a cleaning situation?

What signals are used by different cleaners and clients wishing to terminate a cleaning situation?

How do the different cleaners and clients learn to interpret these signals?

What routines do the cleaners and clients go through during a cleaning situation?

What kind of location and situation do cleaners and clients favour?

Which species of clients do the different cleaners prefer?

Which species of cleaner do the different clients prefer?

Do any fish species mimic any of our SA cleaner fish species?

Studies to answer all of the above questions are ongoing and will be reported on later.

A Dusky Morwong at a cleaning station?

(Taken at Port Noarlunga reef by Steve Reynolds)