Sue Simmonds recently sent me the following email message regarding her late father’s love of the Shandon: –

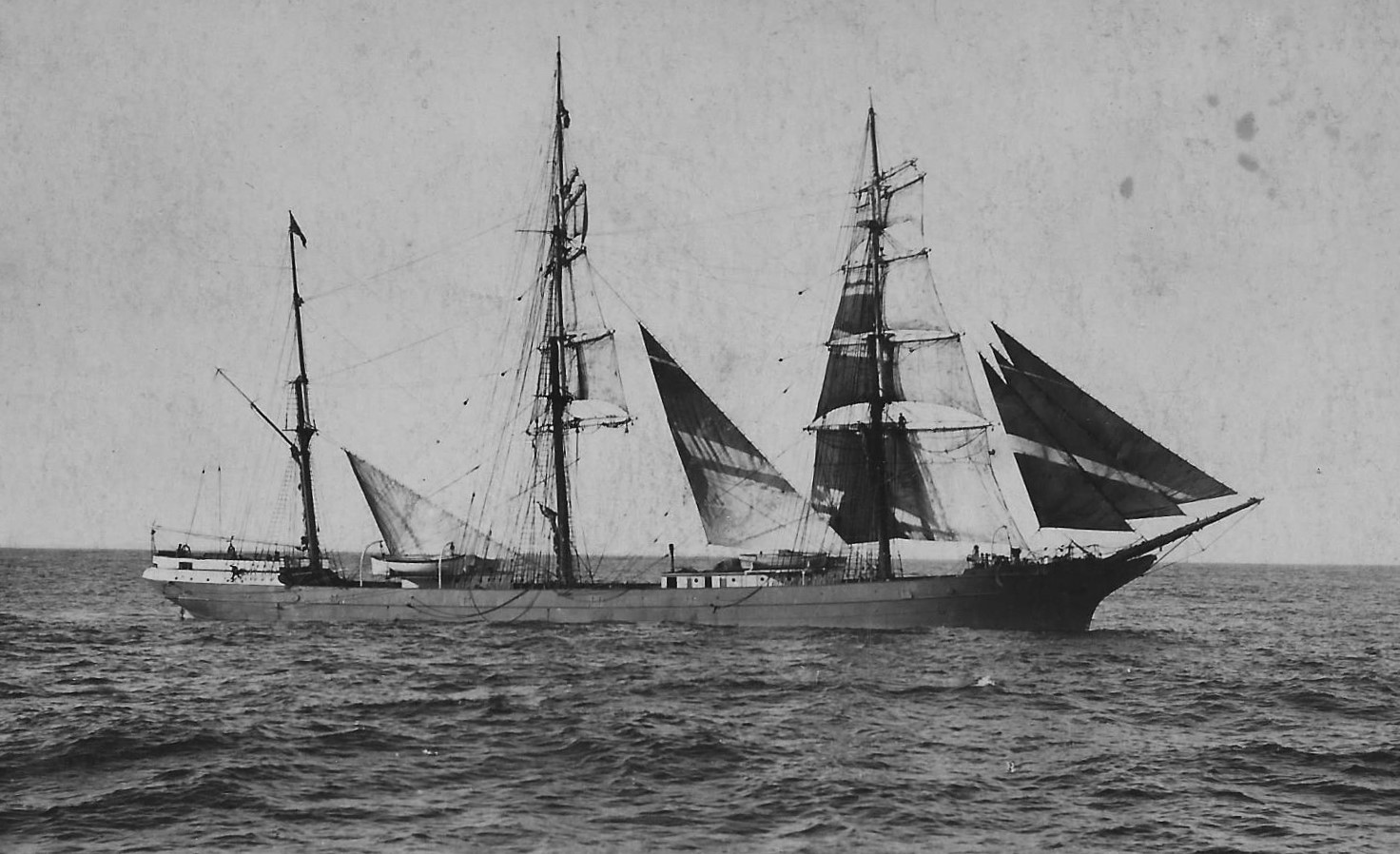

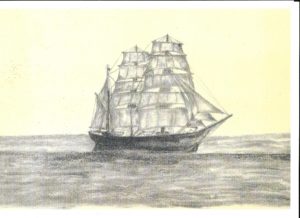

“Hi Steve, The “Shandon” was dad’s favourite ship, he loved sail and was probably born fifty years too early. I’ve also attached a photo of the “Shandon” taken from the “Mount Stewart” off the Coast of Chile in 1918 as mentioned in the story, also a copy of a sketch that Dad did of the “Shandon” plus the letter from the Master of the “Iron Pacific” about the scattering of Walter Rignold Marshall ashes.

There is a story of the voyage from Melbourne to Chile and then the continuation of the journey home to Melbourne.

Considering this voyage was before the Armistice, I don’t think it ever entered his mind that they may have been the target of German U-Boats. In 1918, he sailed to the UK in a German merchantman (which had been claimed as a war prize in Australian waters), via Durban, Dakar to London also before the Armistice. Dad was born in December 1901 and was sixteen at the time of these voyages, you have to admire the naivety of youth.

Cheers, Sue Simmonds”

The message was accompanied by the following details: –

THE “SHANDON” & THE “MOUNT STEWART”

(1918)

Mejillones, Chile, was a big open bay surrounded by land and absolutely devoid of any trees or greenery. As far as the eye could see, towards the foothills of the Andes, was the Atacama Desert.

We were anchored well off-shore at the far southern end of the bay, near what appeared to be a small village of shacks; the homes of the salt-petre miners and workers. Also at that end of the bay, and near the village, were some half dozen large German windjammers. They had been caught there at the outbreak of the war and interned with their crews on board. Half way between our ship and the shore there was anchored the rigged down hull of one of the old Royal Navy “wooden walls of Old England”, like Nelson’s Victory. Her name was the “Liffey”, and she was the home of the Harbourmaster cum stevedore. I cannot remember his name, but I do remember him as a broad Scot.

* (The “Liffey” was an ex-Royal Navy ship built in 1856 and sold to Chile in 1878.)

There came a morning when a beautiful full rigged ship was seen approaching the bay. She was under all plain sail, and with her black and white painted ports was really something to see. She came into the bay a hive of activity, with the crew methodically reducing sail and finally “rounding up”; dropping anchor a little closer inshore, and a couple of cable lengths from us. She was the beautiful “Mount Stewart”, and the odds against her and the “Shandon” meeting in this out of the way place must have been astronomical.

A sketch by Walter Rignold Marshall (said to be of the “Shandon”)

(Courtesy of Sue Simmonds)

Our Master, Captain Gerard, had served in her years before as an officer under her present Master, Captain McColm, who had been Master of the “Mount Stewart” for some years; and was to continue to be so for some years longer. However, the unusual thing about it was, Captain McColm and Captain Gerard were married to sisters. They had lived at Birkenhead, where their father was a boat builder (by the name of Lewis). Happily, for those concerned, both captains had their wives with them. Also on the Mount Stewart was Lorna Lewis, a niece of the Master’s wife; a young lady of about seventeen. It must have been a wonderful coincidence for them to have met like that. It also made life a little more pleasant for us too, as the crews of both ships could visit, hold sing-a-longs, and tell tales on lovely semi-tropical evenings, thus breaking the monotony of daily toil and no shore-leave. We didn’t particularly hanker to go ashore as the old hands told us one didn’t need to look sideways to be picked up by a vigilante, and so spend the night in the vermin infested calaboose. Well, it was a real family gathering between the two ships, and four apprentices took alternative days standing by in their uniforms to man the Master’s gig, and so row him ashore on ship’s business or over to the other ship for pleasure.

We were in port well over a couple of weeks before we looked like getting any cargo, although we were rigged and ready to receive it. At last, a barge with bags of salt petre was brought alongside, and we began loading this for’ard and aft until we had enough stiffening to allow us to unload our ballast.

The method of loading and unloading on the West Coast was archaic, yet slowly efficient considering there was no power. We called it “Armstrong Patent”, simply a dolly winch, bull rope, muscle power, and two men on each winch handle, one on the rope brake, one standing by and spelling each man in turn, and the Second Mate handling the bull rope at the hatch coaming.

The bags of salt petre were much heavier than a bag of wheat, and were loaded one at a time. A bucket of oatmeal water with a pannikin stood alongside the winch, for refreshment. Only two “Chileano’s” were supplied, one to sling the bag on the barge and the other in the hold to stack. Being so heavy, it was stacked pyramid fashion, and this lone man in the hold was good to watch. Once he dropped that bag he never had to shift it, it was in place and solid. Then the gear was reversed to unload ballast into the barge. The procedure was the same only we, the crew, were in the hold shovelling the ballast into large coal baskets. The loading went on for some weeks and, without any shore leave, naturally became very boring.

The day finally arrived when we were down to our plimsoll mark. We were now busy getting the sails up from the sail locker, sending them aloft, bending them, reeving off running gear, and checking the standing gear. The “Mount Stewart” also appeared to be “down to her marks” and was also bending sail.

The activity of the Masters’ visits between both ships increased, and word got out that both ships were to get under way at the same time and stage a race out of the bay. This created intense excitement, and both crews were looking forward to it.

Then, one morning, with a fresh breeze from the north blowing into the bay, all hands were called to man the capstan on the foc’sle head and to heave short the anchor cable. Signals passed between the two ships and it could be seen the crew of the “Mount Stewart” were similarly occupied. Then the singing began, and “Rolling Home” and “Shenandoah” echoed across the bay. Some of those men had melodious or stentorian voices, and it still lives very vividly in my memory.

While this was taking place, four boys were sent aloft to cast gaskets off and let the sails hang in the buntlines, ready to sheet home as soon as the anchor was aweigh. Two of us went up the foremast and two up the mainmast, starting with the courses and up to the upper t’gan’sl. We made the gaskets up and made them fast to the “jack-stay”* as we cast each one off. The headsails and spanker were next. Braces were thrown off the bollards, and coiled down “Flemish coil” ready for running halliards off their pins and ready for hauling.

* (Some sailing terms such as “jack-stay” are explained at the end of this article.)

Then came the cry from the Mate, “Anchor aweigh, Sir!”, and the reply came back “Haul away foretop-mast stay’s’l halliards. Sheet home fore and main lower top’sls.” The anchor was left hanging on the cable at water level, with the carpenter standing by to let go if it was necessary.

It was customary, when making sail, for the First Mate to take the port watch to the mainmast, with the Second Mate at the foremast with the starboard watch. It was also usual for the oldest able seaman to go to the wheel. As the ship gathered way, and the lower top’s’ls filled, she tended to “fall off”, so we were busy at the starboard braces bracing the yards up. The “Old Man” told the helmsman to keep her “full and by”, at the same time bawling “fore and main upper top’s’l halliards!”.

The team work of the crew was something to see. Each man and boy knew exactly what he was doing, and while a couple threw the buntlines, leechlines and clewlines off the pins, others were already on the halliards, hauling upper top’s’l yards up, to the tunes of “Reuben Ranzo” and “Whiskey for My Johnny”.

At the order of “Belay all that! Set your t’gan’sls” the same procedure went on with these four sails, and the spanker and gaff top’s’l set. We were now under most of our plain sail. Meanwhile, the same work had been taking place on the “Mount Stewart”, and she was close on our heels to wind’ard of us and doing a little better than we, which was not to be wondered at, as being a full rigged ship she carried more sail on her mizzen than our barque rig.

We did not have much respite, and were kept busy clearing the decks of a conglomeration of ropes, some to go on the belaying pins, others to be coiled down ready for running when we tacked ship. The Captain, watching very closely, shouted to the Mate “All ready to go about, Mister!”, the Mate and the Second responding “All ready sir”. Then, to the man at the wheel, “Let her run off a little” as this was to get a little more way on the ship.

We were all tense and excited, and ready to move fast. We all knew that speed was essential to tack ship in enclosed waters.

Once again the Captain’s shout echoed, “Ready about! Lee-oh!” and, to the man at the wheel “Hard down your helm”. As the ship came up “into the wind” the fore yards were caught aback, and as she started to “pay off” in the opposite direction, the braces were thrown off the starboard bollards. To the shout “Fore bowline!” the crew began running, taking in the slack of the port braces as the wind pushed the fore yards around. Then, to the cry of “Mainsail haul!”, the sails on the main mast, which were “caught aback”, were hauled every inch of the way around by hand. The headsail sheets were thrown over the stays, the spanker sheets hauled tight (all by hand), and we were away on the starboard tack, still followed closely by the “Mount Stewart”.

On reaching the end of this tack, the same procedure was followed to go about, this time on the port tack, and our third leg across the bay. This was when a very unusual event occurred, involving the “Mount Stewart”. As she “came into the wind” to follow us on the third leg, and having gone closer inshore, she “missed stays” and was actually “in irons”. This meant she had not “payed off”, and she was perilously close to drifting ashore.

Her crew were frantically busy hauling on the starboard braces when, after what seemed an eternity, her sails filled, and she started to make headway. With her yards half braced, she sailed “free”, straight out of the bay, while our ship made one more tack before clearing the headland. We learned later that the answer to this was that she had caught an eddy of wind, blowing off the cliffs. This had saved her going aground and, of course, won her the unofficial race hands down. I remember our Captain pacing the poop and exclaiming “My God, Alex!” when she had missed stays, and he was very concerned for her. However, as they say, “all’s well that ends well”, and her crew were very jubilant at beating us.

One had to experience it to realise the amount of work entailed for the crews of both ships. While it was daylight, we sailed in company, within hailing distance, and at night-fall hauled away from each other. We sailed in company for three days and nights, and close enough at times for photographs to be taken and floated to each other in cans made water tight. The memory of this will remain with me forever.

A photo said to be of the “Shandon”

(and taken from the “Mount Stewart” off the Coast of Chile in 1918)

(Courtesy of Sue Simmonds)

The beauty of a sailing ship with all sails drawing, as seen from another ship, is something that is hard to describe. It must be seen for one to fully appreciate the remarkable beauty of these vessels. As John Masefield put it, “Man shall not see such ships as these again”.

On the early morning of the fourth day, farewells were shouted, and both crews joined in singing “Rolling Home”. We parted company, and the “Mount Stewart” “squared away” for Cape Horn and across the Atlantic to Cape Town. We headed down the Pacific for Melbourne.

Walter Rignold Marshall

Sailing terms:

Braced up. When the yards are hauled round on to the backstays for a wind before the beam.

Braces. Wires and tackles with which the yards are secured.

Buntlines. Ropes attached to the foot of the sails, which extend down to the deck through blocks for hauling the sail close up under the yard.

Clew garnet. A tackle from the clew-iron of a course to the yard for hauling up the corner of the sail.

Clew-iron. An iron spectacle frame in The lower corners of a square sail to which the sheet and clew garnet are attached.

Clewline. Tackles from the clew-irons of smaller square sails to the yards for hauling them up.

Full and by. Sailing with the yards braced up and the sails full.

Gaskets. Lengths of small rope spliced around the jackstays for securing the rolled-up sail to the yard.

In irons. Sails on foremast full and those on main mast aback, preventing movement back and forth.

Jack-stay. A steel rod along the top of the yard to which the head of the sail is secured.

Wear Ship. The manoeuvre of turning the ship around before the wind, keeping the sails full.

(Taken from an unpublished manuscript titled “The Gypsy Seafarer” – Copyright, Susan Simmonds.)

I wrote to Sue seeking clarification about the above photo and sketch, both said to be of the Shandon: –

“Hi Sue, Are you sure that:

the photo is of the “Shandon” (taken from the “Mount Stewart” off the Coast of Chile in 1918)

and

the sketch is of the “Shandon” ?

The sketch looks more like the “Mount Stewart”

and I have a copy of that photo as the “CJS” formerly the “West Glen”!

Sue’s response was, “Dad’s written on the back of the photo, which was developed at Williamstown, “Three masted Barque “Shandon” on which I served my apprenticeship leaving Mexillones on a voyage to Melbourne 1918″, he has also written on the bottom of the sketch “Barque Shandon”. The “Mount Stewart” was full rigged and “port” painted, the sketch is of a ship barque rigged and again he’s written on it “Barque Shandon”. There are photos in the SLV collection of the “Shandon”, in one she is “port” painted and some other slight variations, which was probably her original condition, but the later photos are the same as the one I sent you. They probably didn’t take that much trouble with the painting when she was re-rigged in 1918. Dad was so familiar with the “Shandon” that he recognised her as a hulk in Townsville Harbour in 1943. There are similarities between the photo of the “Shandon” and the photo on the wreck site of the “C.J.S.” ex “West Glen” but I put that down to the general design of Barques at that time. The “C.J.S.” ex “West Glen” sunk off Mauritius in 1920.

I do accept that dad’s memory of dates was a bit muddled when he was in his 80’s, but the sketch and photo had been around for much longer than that.

Hope the above helps. Cheers, Sue “

Sue later added, “Actually the “Shandon” was “port” painted in 1934 when it was re-rigged for the Centenary Maritime Exhibition. There’s a photo in Trove.”

My response to Sue was, “Yes that helps thanks. You say that the Shandon was re-rigged in 1918. That ties in with a photo of her on page 120 of “Sail in the South” by Ronald Parsons.

That photo that you sent to me, however, is on page 33 of the book as the CJS/West Glen.

The Mount Stewart is on the same page. The book agrees that the “C.J.S.” ex “West Glen” was wrecked off Mauritius in 1920. Mexillones is actually ‘Mejillones’. It is near Antofagasta.”

Sue quickly replied, “Hi Steve, I think Mr Parsons got it wrong with the photo of the “C.J.S.” ex “West Glen”, there is a photo on SLV (State Library of Victoria) of the “C.J.S.” and if you compare it with the photo of the “Shandon” there are differences, the bowsprit, deckhouse, the extra protection around the stern rail.”

Re Mejillones, Sue said, “Dad spelt it Mexillones, I think simply because the “j” is pronounced “h” like you’re trying to spit something out, and everyone would ask him what the hell he was saying. Mejillones is on the edge of the Atacama Desert and they run the Paris-Dakar race near it every year, through Antofagasta.”

According to “Sail in the South” by Ronald Parsons, the Shandon was a ‘workhorse of the sea’. He says that she had a chequered career. He states that she was built at Port Glasgow in 1883. She was an iron ship of 1442 gross tons. Her name was changed to the Victor when she was sold to Norwegian owners. She carried Baltic timber to Sydney & Newcastle, Australia in 1914, after which she was sold again. Her new owners used her as a coal hulk after removing her masts. In 1918, when ships were running short, the Commonwealth Government bought her and re-rigged her as a barque. She was then re-named the Shandon again. It was about this time that Walter Marshall sailed on her. She became a coal hulk once more in 1922 after being sold again. Walter Marshall recognised her as a hulk in Townsville Harbour in 1943. She was eventually broken up in about 1960.

Also in “Sail in the South”, Ronald Parsons says that the Mount Stewart was a steel ship of 1903 gross tons built (at Glasgow?) in 1891. The Cromdale was her sister ship and the two vessels “were the last two sailing ships built specially for the wool trade from Australia”.

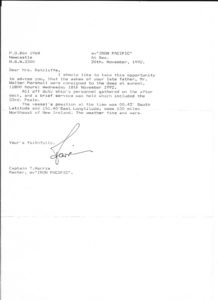

As explained by Sue in my article titled “Follow-up on the Schooners Lemael & Booya” (see https://mlssa.org.au/2016/09/09/follow-up-on-the-schooners-lemael-booya/ ), “When my dad died in 1988, his request was that his ashes be scattered at sea. However, I was unable to part with the ashes and they sat on by kitchen bench until 1992. I owned a taxi in Newcastle, and one day I was taking a seaman back to the BHP wharf and I was telling him my dad’s story and in particular his last request. The gentleman said to me that he could organise that request and that if I had the ashes and a short precis of dad’s life at the wharf at 7 am the next morning it would be done. His only other question was where did I think it appropriate to attend to the task and my answer was somewhere warm. I was rather caught on the hop, but I duly delivered the ashes to the ship. Approximately three weeks later, I received a letter from the Master of the “Iron Pacific”, the largest BHP ship at the time, “at sea”, and it stated that the off watch had assembled on the afterdeck and the 23rd Psalm was read and the ashes scattered. The letter listed the longitude and latitude, which was just south of the Equator near New Britain, where dad had actually been during WW11. Oddly it gave me a sense of place.”

Sue has now provided a copy of the letter from the Master of the “Iron Pacific”: –

The letter from the Master of the “Iron Pacific”

about the scattering of Walter Rignold Marshall’s ashes

(Courtesy of Sue Simmonds

Message for SueSimmonds:Hello, I have just read your post on the Barque Shandon and the Ship Mount Stewart in which you mentioned the Liffey being anchored in the Bay of Mejillnes in Chile which your father visited. I can tell you a little about the frigate the HMS Liffey as my mother’s grandfather lived on the ship and was the port superintendent if you are interested.

Regards,

Myra

Thanks Myra, did you ever hear from Sue? We will pass this on to her for her response.

A photo of the wrecking of the Cromdale can be found at http://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/06/02/46282-3-2/2 with the comments “A British built iron sailing barque, The Cromdale, ran into Lizard Point, the most southerly point of British mainland, in thick fog. The three-masted ship was on a voyage from Taltal, Chile to Fowey, Cornwall with a cargo of nitrates.”

Hi my great grandfather was Master mariner Alexander gerard and i have the same picture as this one but with the sails up.

Thanks for letting us know about your great grandfather and the photo Christin. If you can send us a copy of the photo, we will post it to our website.