It is with mixed feelings that I frequently see people I know raving about their next dose of international ecotourism, be it diving with whales in Tonga or on tropical reefs in any of our Pacific island neighbours’ waters. On the one hand, I respect my peers enthusiasm for diving, for exploring the natural world and for seeking out intimate experiences with the living ocean. On the other, I have grave concerns that the same people may not spare a thought for the impact of their international travels- the flight leg in particular.

I would like dive tourists to consider the direct contribution that flight miles traveled makes to climate change. The most obvious threats this poses to our northern neighbours are widely known and well documented. As atmospheric carbon dioxide continues to increase, sea levels are rising and entire island nations (Tonga and the Maldives are two prominent examples) will in time disappear beneath the briny blue.

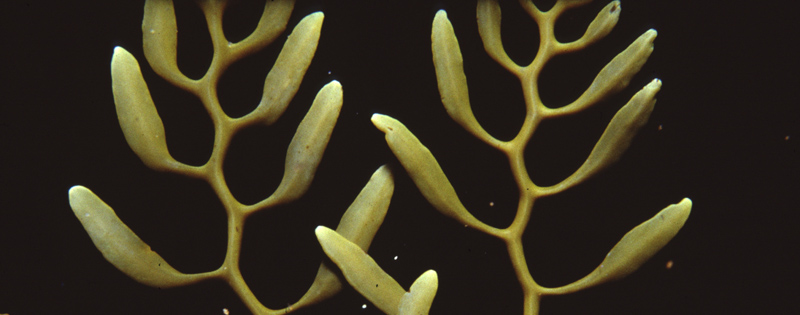

For the region’s beloved tropical reefs themselves, they face an equally unpleasant fate, as oceans gradually acidify. As this trend continues, hard corals will ultimately be unable to build their calcium-based structures, and glorious coral reefs will become boneyards of algae-covered memories in the years ahead. These graveyards may not even be able to support crustaceans and some gastropod mollusks as they will face the same difficulties when attempting to grow their exoskeletons or shells in increasingly acidic water.

To bring this topic closer to home, I used a few publicly available tools to roughly quantify the flight-related carbon emissions of dive tourism. The examples I chose all involve flights departing from my hometown of Adelaide, in South Australia. The first tool I used (courtesy of Carbonfootprint.com) estimates the carbon footprint of the flight. The second (courtesy of the US Environmental Protection Agency) gives examples of equivalent activities which would:

- produce the same quantity of CO2 emissions, and

- sequester (store) the carbon emitted

I wrote this post in the hopes that dive tourists might begin to ask themselves a number of questions, including:

- Do I really need to travel so far to dive on a coral reef, or with turtles, rays or whales?

- If I truly love coral reefs and tropical oceans, am I able to plant enough trees to sequester the carbon I emitted getting there?

- Alternatively, can I afford to make a suitable, equivalent donation to an organisation which has the capacity to plant enough trees to do so in my absence?

I hope divers consider the data in the table below and start thinking about their activity and its implication for the future health of our oceans and our Pacific neighbours’ homelands and culture. If you have already booked your next dive holiday and are curious about the carbon footprint, feel free to use the widget below the table and share the results in the article’s comments below.

| Flight from Adelaide, South Australia (ADL) to | Destination | Metric tonnes CO2 emitted per return economy passenger | No. trees grown from seedlings for 10 years required to sequester released carbon | Equivalent emissions measured in standard car kms |

| Dubai (DXB) | Dubai, UAE | 1.75 | 44.9 | 6667.2 |

| Phuket (HKT) via Kuala Lumpur (KUL) | Phuket, Thailand | 1.02 | 26.2 | 3886.4 |

| Kuala Lumpur (KUL) | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | 0.91 | 23.3 | 3467.2 |

| Singapore (SIN) | Singapore | 0.86 | 22.1 | 3276.8 |

| The Settlement (XCH) via Perth (PER) | Christmas Island | 0.79 | 20.3 | 3009.6 |

| Fua’Amotu (TBO) via Melbourne (MEL) | Tonga | 0.78 | 20 | 2971.2 |

| Nadi (NAN) via Melbourne (MEL) | Nadi, Fiji | 0.72 | 18.5 | 2742.4 |

| Bauerfield (VLI) via Melbourne (MEL) | Port Vila, Vanuatu | 0.64 | 16.4 | 2438.4 |

| Ngurah Rai (DPS) | Bali, Indonesia | 0.6 | 15.4 | 2286.4 |

| Cairns (CNS) | Cairns, Queensland | 0.36 | 9.2 | 1371.2 |

| Ceduna (CED) | Ceduna, South Australia | 0.09 | 2.3 | 342.4 |

| Port Lincoln (PLO) | Port Lincoln, South Australia | 0.04 | 1 | 152.32 |

| Whyalla (WYA) | Whyalla, South Australia | 0.04 | 1 | 152.32 |

| Kingscote (KGC) | Kingscote, South Australia | 0.02 | 0.513 | 76.16 |

On seagrass as a carbon sink

When I broached this topic on Facebook today, a friend reminded me that seagrass is another excellent carbon sink- indeed their losses are often compared to deforestation on land, though the drivers are different. While seagrass revegetation projects could be another way to mitigate carbon emissions from flights or other CO2 emitting activities, much of the seagrass lost in South Australia will struggle to be regenerated by seeding or planting. This is because the root causes of the seagrass loss persist. The primary drivers of seagrass loss in SA are poor stormwater and waste-water management- most notably heavy discharges from metropolitan Adelaide directly into Gulf St. Vincent.

There are some people working on seagrass regeneration and revegetation projects around the world, and in my opinion they would make worthy recipients of donations from interested dive tourists looking to mitigate their carbon footprints. They may even have opportunities for divers to volunteer to assist them in the water. Seagrass Restoration Now is one such group. The work is still quite experimental, and requires improved or improving water quality in the area in order to succeed. Some additional information on seagrass revegetation techniques can be found here.

During that brief period during which Australia had a price on carbon ($23 per tonne), seagrass meadows were able to be evaluated economically value for the first time (not to discount their other known value as critical fish nursery habitats). The seagrass meadows of Shark Bay in Western Australia, which have not suffered from poor watershed management the way many other Australian seagrass meadows have, were thus valued at $8 billion. The figure was arrived at by multiplying the bay’s 400,000 hectares of seagrass by the average carbon storage estimate of 884 tonnes of CO2 per hectare. With or without a carbon price attached, the total carbon storage capacity of Shark Bay is estimated at 350 million tonnes. When we speak of ‘ecosystem services’ that nature provides for the benefit of life on earth, this one is a whopper.

It’s time our significant seagrass meadows in South Australia received a similar evaluation and the positive attention they deserve. Meanwhile, why not plan a seagrass dive in Spencer or St. Vincent Gulf, and spend some time reflecting on the carbon footprint of your underwater adventures?

Great,Dan!Very informative,and as you know,I love seagrass diving,and we’ve such a plethora of safe,shallow beautiful grass dive sites here in our gulfs.